On March 11th, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan Act, which includes provisions that will cut child poverty in half if they become permanent. This Act is a historic opportunity to reduce child poverty and to do it in an equitable way. As a scholar of child wellbeing and racial and ethnic equity, and a member of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine committee that put together the 2019 consensus report, A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, I am delighted by our nation’s commitment to invest in our children. However, because the American Rescue Plan does not fully address eligibility restrictions on immigrant families and their children, 91% of whom are American citizens, the American Rescue Plan will not cut child poverty in half for all children.

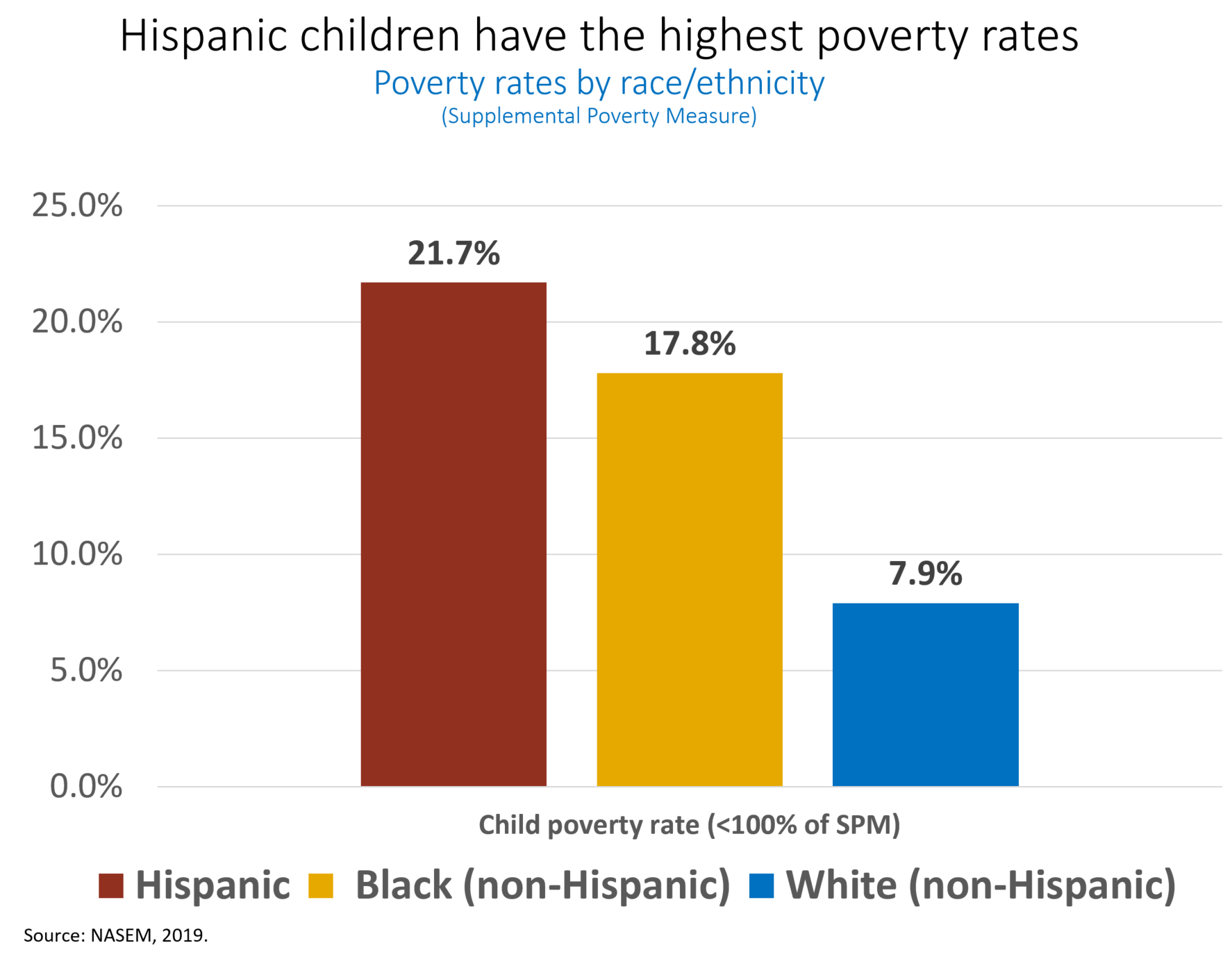

Child poverty is an enduring shame of the United States. According to the Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, 13% of children live in poverty. Hispanic children have the highest child poverty rates (22%) followed by Black children (18%). White children have a poverty rate of about 8%. At the individual level, child poverty, especially persistent poverty, causes long-term negative education, health and economic outcomes. And as a country, child poverty costs our economy 4 to 5 percent of GDP per year (between $800 billion and $1.1 trillion).

For these reasons, Congress tasked the National Academies with mapping a path forward to reduce child poverty by half in the next ten years. The consensus report examined 20 individual policy changes and four policy ‘packages’— combinations of tax credits, nutrition and housing assistance, and a new child allowance program modelled as an expansion of the Child Tax Credit. The report concluded that although all the policy options would reduce poverty for all groups, Hispanic children and immigrant children would benefit less.

The reason is that many immigrants, including immigrants lawfully present in the U.S., have restricted eligibility for anti-poverty programs, which hurts their citizen children. Even when families meet eligibility criteria—such as being low-income and working—children in immigrant families have restricted access because the safety net is tied not to the child’s needs, but to the parent’s immigration status.

Hispanic children are disproportionately hurt by immigrant eligibility exclusions

Eligibility restrictions based on immigrant status disproportionately hurt Hispanic children, who make up about 25 percent of the child population and growing, and are the largest group of children in poverty: 41 percent of all children in poverty are Hispanic (about 4 million). Even though 95 percent of Hispanic children are U.S. citizens, more than 50 percent have at least one foreign-born parent, and about 25 percent have an undocumented parent. Although their parents have higher employment rates than other adults, they tend to hold low-wage jobs, which, in combination with restricted access to the safety net, puts their children at high risk of poverty.

The American Rescue Plan is great for many American families. It dramatically expands the Child Tax Credit, provides most families with stimulus checks, and expands the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). But to benefit the most vulnerable children and reduce poverty in an equitable way, the policy changes should expand eligibility for children in immigrant families. The EITC and the Child Tax Credit are among our most important anti-poverty programs. Without these tax credits, the child poverty rate would be 18.9% instead of 13%.

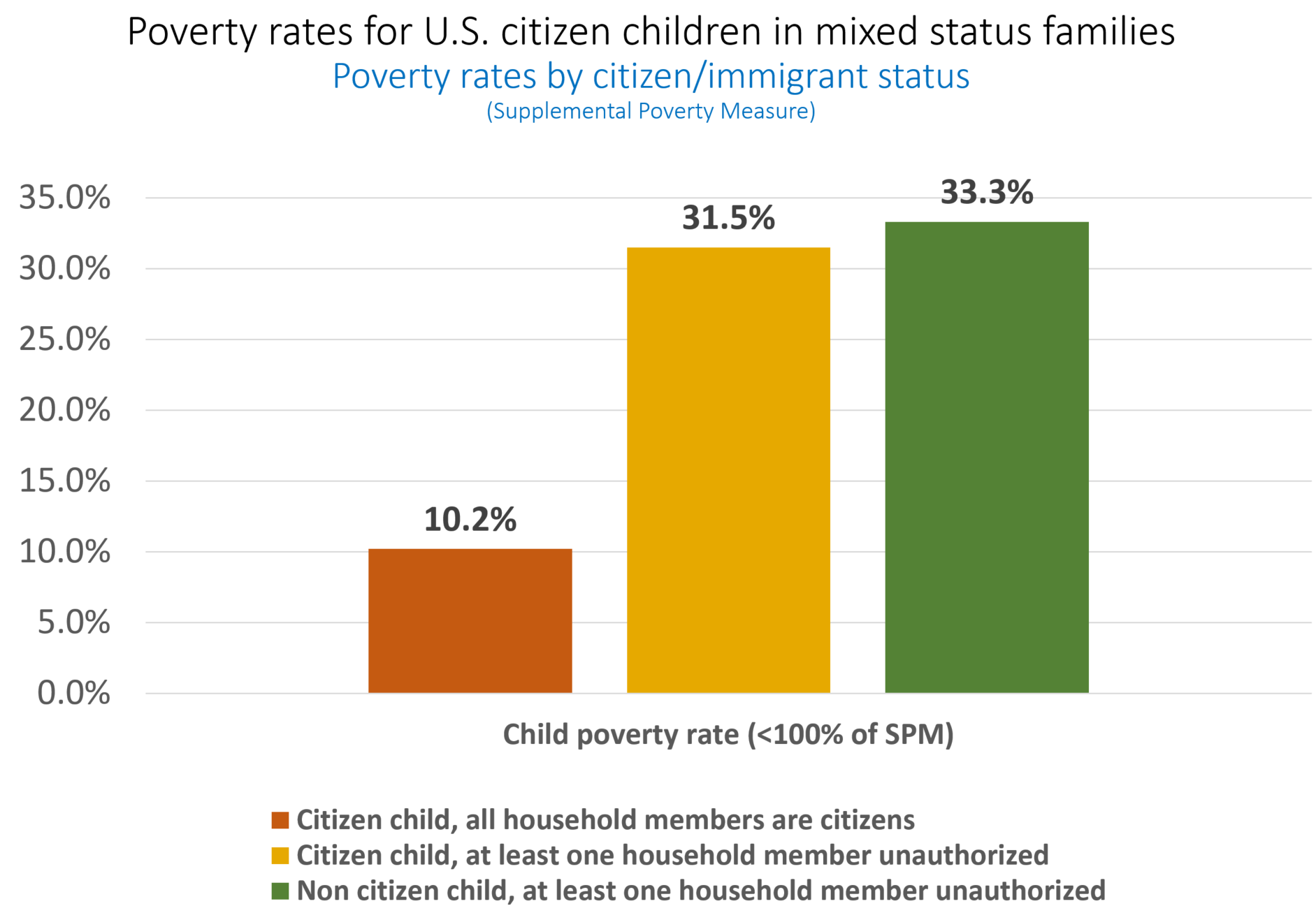

However, the EITC--arguably our strongest anti-poverty tool--excludes U.S. citizen children if even one parent lacks a Social Security Number. Thus, although the EITC is meant to help families with children, it leaves out about 17% of U.S. citizen children in poverty because they live in mixed-status families with parents who file their taxes without a Social Security Number. Children in mixed-status families have much higher poverty rates (31.5%) than children in all-citizen families (10.2%).

Without making the EITC available to all citizen children—regardless of how their parents file taxes—even generous expansions of the EITC will completely leave out this large and vulnerable group of citizen children. Indeed, the National Academies report showed that increasing the EITC by 40% would reduce poverty by 20% among children in all-citizen families but only by less than 3% among U.S. citizen children whose parents lack Social Security Numbers.

We can model expansion of eligibility of the EITC for children in immigrant families after the stimulus payments in the American Rescue Plan. Originally, the CARES Act denied stimulus payment entirely to families with U.S. citizen children if even one parent did not have a Social Security Number. This excluded 3.7 million U.S. citizen children and 1.4 million U.S. citizen spouses from stimulus payments. A public outcry and dedicated advocacy have rectified these exclusions—U.S. citizen children are eligible to receive $1,400 stimulus payments under the American Rescue Plan, regardless of whether their parents have a Social Security Number. We must make similar changes to the EITC: making all U.S. citizen children eligible regardless of how their parents file taxes, in order to achieve equitable reductions in poverty for all children.

Restore the Child Tax Credit to pre-2018 standards

An important feature of the American Rescue Plan Act is that it expands the Child Tax Credit to include very low-income families and to increase the amount of the benefit. These changes are commendable and can go a long way towards reducing child poverty. But for the poverty reduction effects to be equitable, eligibility of all children in immigrant families must be restored. Until 2018, children without Social Security Numbers themselves, mostly undocumented children, were eligible for the Child Tax Credit. The 2018 tax law made them ineligible, cutting out roughly 1 million children who have a very high poverty rate of more than 30%. According to the National Academies report, even a child allowance—essentially an expansion of the Child Tax Credit—of $3,000 per child per year would not do anything to reduce poverty among these children, because their eligibility was cut in 2018.

Improving access to the safety net for children in immigrant families in not only the right thing to do, it also makes practical sense. In the short term, our economy cannot recover equitably if we kick the ladders of opportunity out from under our most vulnerable children. Longer term, an investment in all kids today, including kids in immigrant families, is an investment in future American workers and citizens.

I support the strong measures in the American Rescue Plan to reduce child poverty and hope they will become permanent. However, without addressing exclusions that target immigrant families, we will not be as effective in reducing child poverty, we will not cut poverty fairly and justly for ALL children, and we will continue hurting U.S. citizen children in immigrant families. The American Rescue Plan Act holds the promise of transformational change for children. But in order to live up to that promise, we must avoid further entrenching racial and ethnic inequities, which is what will happen if we deliberately choose to exclude children in immigrant families from our nation’s recovery and safety net.

The Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) extends the official poverty measure by basing the poverty threshold on the expenditures U.S. families must make for food, clothing, shelter, utilities and other needs and by taking account of the resources government programs provide to assist low-income families.

Watch: Promoting the Health and Well-Being of Children in Immigrant Families, a webinar co-hosted by NASEM's Forum for Children's Well-Being and the Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy